Job shops are always very difficult to manage. As I described in my previous posts, the irregular material flow causes fluctuations that are very hard to contain. In my view, the only true fix for a job shop is to convert it into a flow shop. In this post I will talk a little bit about how you approach the idea of converting a job shop into a flow shop … although this is not always possible. However, in many cases it is possible to increase flow-shop-like segments, even though the whole system is still a job shop.

Required: Dedicated Processes

There is one requirement for establishing a flow line: You need processes that are dedicated to the flow line. The processes within the flow line should handle only parts of the flow line. If you have a “flow line,” but parts from the job shop frequently enter the flow line sequence to be processed, then it is not a flow line. Try your best not to have outside parts jump in and out of the flow line, as this will water down the performance of the flow line significantly.

Having said that, let me walk you though a couple of things you can do to move toward flow lines. Below are a few suggestions. These are not necessarily a sequence of improvement steps, but a few ideas that also support each other through iterations. Go though them repeatedly and try to find the best system that you can imagine.

Identify Materials with Similar Process Sequences

The first step in converting a job shop into a flow shop is to identify products with similar process sequence segments. Now, you may be thinking, Dude, if all my products would have the same process sequence, I would have established a flow shop ages ago. First of all, there are indeed still a few plants out there that have such a situation but have not yet converted to a flow shop due to important things like “tradition” or “no time.” But secondly, there is a lot of wiggle room.

The first step in converting a job shop into a flow shop is to identify products with similar process sequence segments. Now, you may be thinking, Dude, if all my products would have the same process sequence, I would have established a flow shop ages ago. First of all, there are indeed still a few plants out there that have such a situation but have not yet converted to a flow shop due to important things like “tradition” or “no time.” But secondly, there is a lot of wiggle room.

True, you may not be able to have a full flow shop right away, but there are quite likely some possibilities in the right direction. Let me repeat my sentence from above with some emphasis: Identify products with similar process sequence segments. The process sequence does not need to be identical for all products, but similar. It also does not need to be for the whole value stream, but it is okay to do it for segments. Every step you take away from a job shop and toward a flow shop helps!

When looking for products with similar process sequence segments, you also would need to keep an eye out for the total workload. It does not help to identify one hundred products with perfectly equal process sequences if they are all extremely rare and make up like 5% of your total workload. Often it makes sense to start with your high runners. Surely you know the Pareto principle, that 20% of your products make up 80% of your sales. If you get even only 10% of the high runners on a flow line, you have gained much ground toward a flow line.

Separate Line for Flow Parts

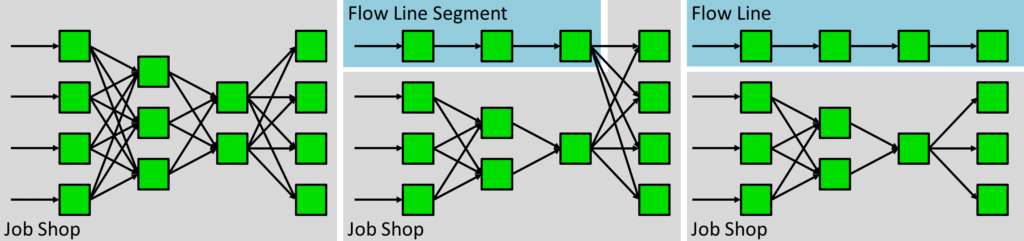

If you have some parts that are somewhat similar for at least part of the sequence, you may establish a flow line for these parts, at least for the sequence where they have a similar process sequence. I have illustrated this below using the example from the previous posts.

Often, sub-assemblies are more suited to flow lines compared to final assemblies, since components often have less variation. Hence, the more-standardized components may be a good a candidate for flow segments.

Skip a Process, Add a Process

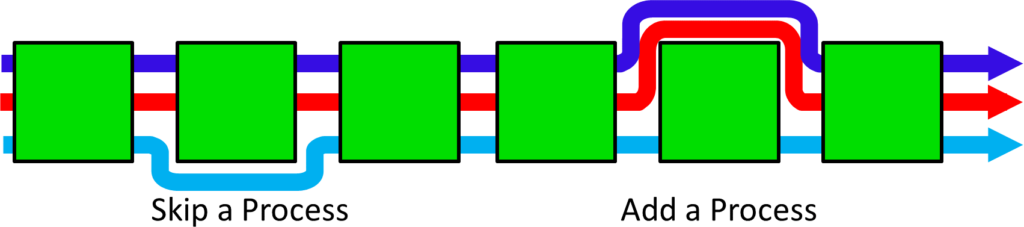

Please note that it is usually not a problem if you have a bunch of similar products but one product does not need one process. In this case, you can still have a flow line. The product in question just moves through the process without being processed. This happens commonly in industry.

Similarly, if there is a product that has an additional step, you may also add this process into the flow sequence. All other products then simply skip this process that is required only for this one product. Many combinations of this are possible (i.e., processes that are required only for half of the products), but not the other half of the products that are produced on this flow line.

The image below visualizes this. However, in this visualization I have the lines for the products go “around” a process. In reality, however, the parts would go through the process, just without being processes.

Hence, you can have processes that are not for all parts. This sometimes solves a problem in establishing flow lines, but creates another albeit often smaller problem, namely how to balance the line. There are different possible solutions. If it is a fully automated process, then we don’t really care about the waiting time of this process. The products that are not processed on this automated machine simply go through, the machine idles, and we don’t care since machines that idle due to lack of demand are very far down on our list of priorities.

If it is a manual process, we can work with the operators moving around different processes. Common examples are bucket brigade, rabbit chase, chaku chaku line, or other similar approaches. In the simplest case for the example above, one worker could move between the two partially used processes to cover them both. For very long cycle times (think hours), you could even assign workers to this process when needed, and elsewhere when not.

This, however, does not work for a fully manned line with shorter cycle times. In this case we may have options with mixed model sequencing, where a part that requires this process is followed by a part that does not require it, and the worker is on average still working well. I have written a very long series of posts on mixed model sequencing if you need more details.

Only if we cannot do automation, partial staffing, or mixed model sequencing would we need a worker who idles until a part comes along, which is not good. Workers having a lot of idle time is a big waste, and it is also disrespectful to the worker.

There are more ideas that will help you in converting your chaotic job shop into a leaner flow shop. I will present these in my next post. Until then, go out, straighten out your material flow into a nice line, and organize your industry!

P.S.: This blog post was inspired by a part in a video presentation by Nampachi Hayashi, which I found through an article by Dirk Fischer. Thanks to all 🙂

Use of Kanban boards are also very useful to visualize flow of work in job shops.

Hi Mario, any kind of visual management will help! For a kanban board, you also would need a kanban type pull system, which I wrote about in other articles. This article focuses on the material flow. Thanks for commenting 🙂

Hi Christoph, I have question about your simulation. Which software do you use to create animations?

Thanks

Hi Rene,

my animations are made in Microsoft PowerPoint. Not because it is particularly well suited to animation, but because I already have all the objects and I know the program well. The animation (often multiple slides) are exported as a video and then converted to a GIF using https://ezgif.com/video-to-gif , including cropping the GIF to size.